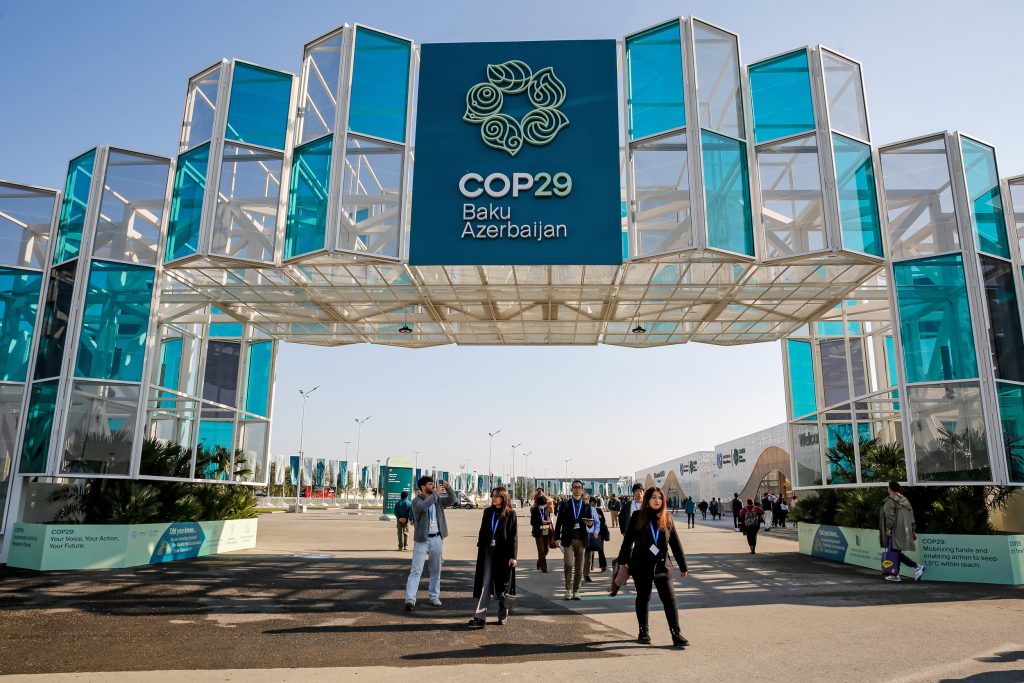

BAKU, Azerbaijan—Under an eye-watering petrochemical smog, the UN’s 29th climate summit—COP29—started here today with brave words, but few specific ideas about how to prevent what many negotiators fear will effectively be the United States dragging the rest of the world off a climate cliff.

While it’s possible for other countries to raise their climate ambitions regardless of what the U.S. does under president-elect Trump, they can’t stop the estimated additional 4 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions his policies could unleash, pollution that would still be overheating the climate hundreds of years from now.

Those 4 billion tons of emissions “are a death sentence for the planet,” said Jamie Minden, senior director of organizing with Zero Hour, a nonprofit climate advocacy group, in one of the first press conferences at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Baku during which global climate advocacy organizations tried to outline a roadmap for climate action in the U.S. and around the world in the years ahead.

Global heating is already approaching 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial baseline, a level at which scientists say some dangerous climate feedback loops are likely to kick in and accelerate warming even more.

“We’ve faced the Trump administration before,” Minden said, explaining that her organization was founded in 2017 alongside other groups facing the policies of the previous Trump administration they deemed damaging to the climate and the environment. “Young people refuse to go quietly into the night.”

The press conference held by U.S. and international climate advocacy groups was one of a number on the first day of COP29 that exhibited the global jitters and confusion elicited by last week’s election results.

“We know that we will face much more extreme opposition over the next four years than we have in the past,” Minden said. “It’s sheer madness that politicians continue to expand fossil fuels and subsidize them, but at this moment, young people are feeling determined. We are fighting for our planet because we are facing some of the worst consequences of the unrelenting greed of these thoughtless politicians, and we are feeling optimism, hope and love.”

Will the U.S. Step up at This Year’s COP?

In Baku, climate activists are looking to the Biden administration to make one last big push for climate action by supporting an ambitious new global climate financing goal, halting subsidies for fossil fuels and taking other steps “to seal a climate legacy and put in a bulwark of protections against Trump’s ravages,” said Ben Goloff, with the Center for Biological Diversity.

“We need to see the Biden administration actually put their money where their mouth is,” he said, adding that the U.S. could still be a constructive force in the development of a new global climate finance plan that is one of the big goals at COP29.

Goloff said one of the most important things Biden could do during the final months of his term would be to go to the meeting of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development in Paris next week with a plan to cut or stop financing for new fossil fuel development projects.

Back in the U.S., Goloff said Biden should fill as many federal court vacancies as he can.

“That is key,” he said. “We need the legal system to be working for us as we fight back against Trump’s devastating attacks on communities. We’ve done it before. We’re going to do it again.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Goloff said environmental groups won about 80 percent of their lawsuits against the first Trump administration.

“We can do that again and we can improve on that,” he said. “Filling federal judicial vacancies is a very durable thing. Unfortunately, we know that very well from the first Trump administration.”

Most existing or new measures blocking various fossil fuel development plans, including natural gas exports and pipelines, can mostly be undone again by Trump, Goloff said, but the new administration would have to “remake the whole case” that the projects are in the public interest.

“That takes many, many months,” he said. “That gives more time for litigation, grassroots pushback, throwing sand in the gears, life-saving time to prevent these mega-polluting fossil fuel projects.”

Developing Countries Seek $1 Trillion in Climate Financing

The U.S. election outcome will also color discussions about climate financing, one of the main topics at COP29. As part of the Paris Agreement, nations globally pledged $100 billion annually to help developing countries speed their transitions to low-carbon economies, and respond to damages they are already enduring from climate change. Developed countries finally met that target in 2022, when they mobilized $115.9 billion, but, that amount has proven woefully short of what is needed, and plans to increase climate financing have been in the works for several years.

“This year is the climate finance year,” said Liane Schalatek, associate director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Washington, D.C., where she spearheads the foundation’s work on funding for the clean energy transition and climate adaptation. Developing countries say at least $1 trillion is needed annually for the energy transition and for climate adaptation, but the expected U.S. reversal on climate policy will make it even harder to reach that goal, she said.

With the prospect that the U.S. might again withdraw from the Paris Agreement and potentially from the UNFCCC itself, she doesn’t think there will be much confidence that any negotiations currently happening could deliver what is needed, she said.

“I was just struck by that almost eerie parallel that we have to the last time,” she said, referring to Trump’s reneging on the Obama administration’s previous commitment of $3 billion to climate finance. She said that, given U.S. politics, it would have been difficult for a Democratic administration to deliver on that promise, but with Trump, she said, “just forget it.”

And that sends a “horribly discouraging message” to other countries involved in the finance discussions, she said.

“If you know that there is no way that the U.S. is going to participate in any shape or form, and that whoever is there in terms of negotiators won’t really have a mandate to negotiate anything, it’s really hard to see how you could entice countries that already feel that they’re going to be stiffed [to negotiate],” she said.

If the U.S. ever had any claim to leading on climate, Trump’s expected rejection of international climate governance as a scam completely undermines it at a “crucial time, when we only have four or five years left in this critical decade for climate action.”

After Trump was elected in 2016, his administration’s position toward the UNFCCC process could be described as one of neglect, she said. But it could be worse this time.

“The question for me is, how destructive can they be?” she said. Under the first Trump administration, U.S. negotiators remained involved in climate finance discussions, “but they stayed quiet or focused on things like transparency and accountability. So they were not really actively trying to hinder or be obstructive in the process.”

The exception, she added, were a few Green Climate Fund board meetings that one of Trump’s political appointees attended.

“He was actually trying to push everybody’s button, to basically rile up people,” she said. “And that, to me, is the difference between benign neglect and sabotage.”

But at this point, nobody knows exactly what to expect from the U.S. at the UN climate talks next year and beyond, so some countries are taking a wait and see approach, and say they will try to work with the new administration in areas where interests overlap, like carbon capture and hydrogen-based energy.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,