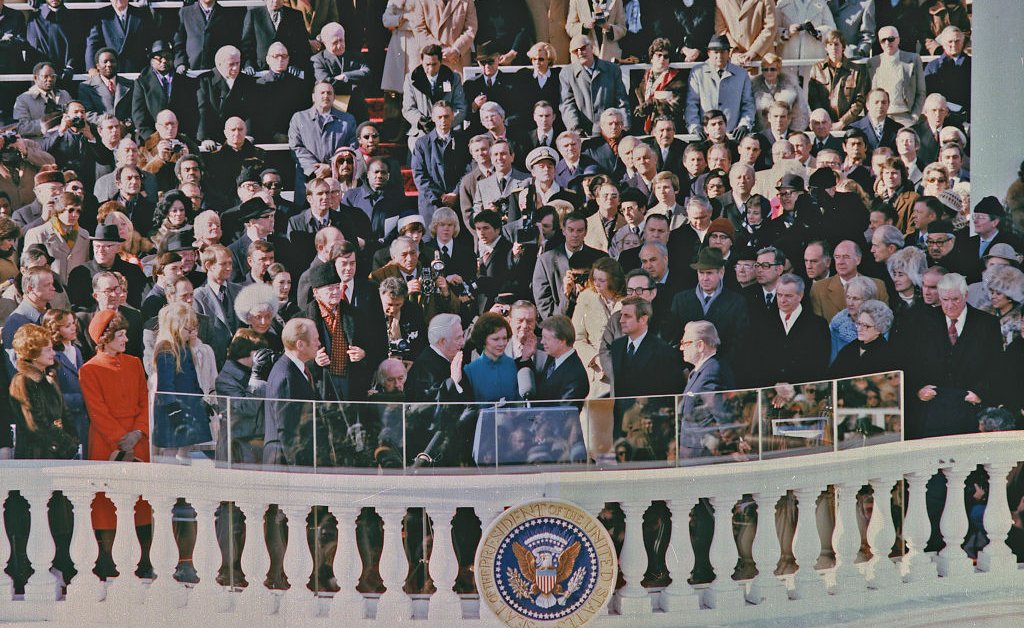

Garth Brooks and Trisha Yearwood are momentarily stepping back into the spotlight.

While the couple have remained largely out of the public eye since an anonymous woman filed a sexual assault…

©2022 DopeReporters. All Right Reserved. Designed and Developed by multiplatforms