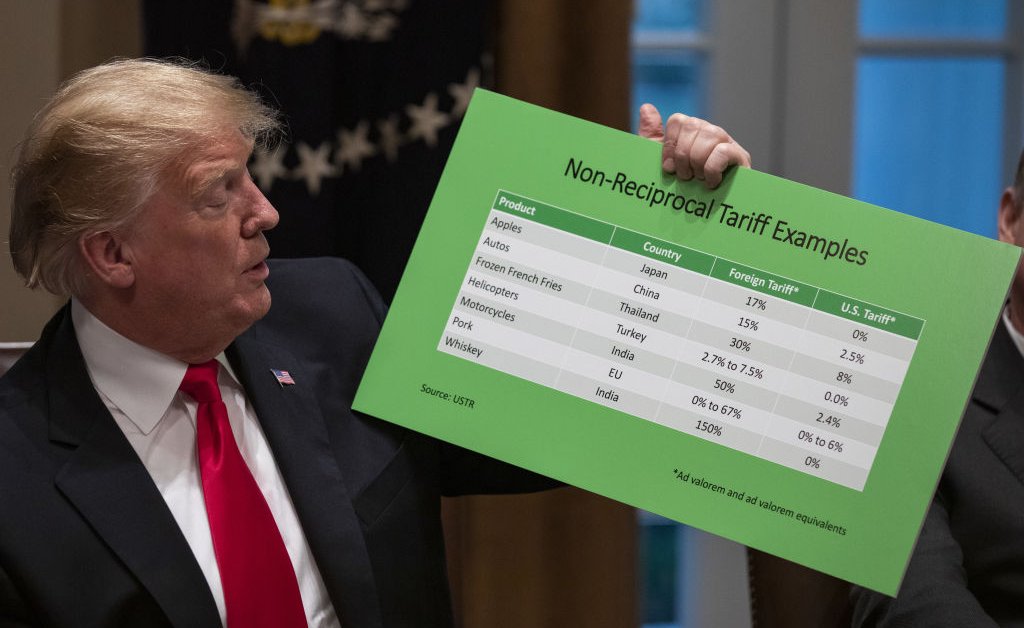

Donald Trump loves tariffs. Last week, he told a Chicago audience that, “To me, the most beautiful word in the dictionary is ‘tariffs.’ It’s my favorite word.” For Trump, tariffs constitute the proudest achievement of his presidency and the engine of economic and social revival. “You see these empty, old, beautiful steel mills and factories that are empty and falling down,” Trump declared. “We’re going to bring the companies back. We’re going to lower taxes for companies that are going to make their products in the USA. And we’re going to protect those companies with strong tariffs.”

Trump’s tariff obsession flummoxes conventional economists, who see it as a potentially disastrous driver of inflation and trade wars. It also draws disdain and ridicule from Democrats; Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen denounced tariffs as deeply misguided.

But tariffs are about more than economic policy. They are also political and rhetorical tools, ones that played a central role in the development of the Republican Party itself. For the generations of Republicans who steered the party from the 1860s until the Cold War, tariffs were the glue that held together a political coalition. Trump has revived that 19th century Republican tradition, once again turning to tariffs as a central unifying principle. Dismissing his tariff fixation as bad economics can miss the point and underestimates the political and cultural appeal of such a vision.

For William McKinley, whose presidency bridged the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, and his fellow Republicans, the protective tariff functioned as the central icon in their pantheon. Like Trump, they saw the tariff as an economic cure-all. It not only shielded American businesses from foreign competition, but also safeguarded the wages of industrial workers and funded pensions for veterans. “I am a tariff man,” McKinley declared during his 1896 campaign. “I run on a tariff platform.”

Read More: Where Donald Trump and Kamala Harris Stand on China

More than anything else, the tariff served a political purpose. It cemented disparate state-level organizations into a potent national coalition. Protection rewarded heavy industry and the regions that supported it: the textile centers of New England, the steel mills and oil refineries of Pennsylvania and Ohio. Special tariff provisions also brought other constituencies, such as Midwestern producers of raw wool, into the Republican fold. Organized labor also worshiped at the altar, finding many of the most protected sectors less hostile to unionization. One union chief, for example, credited the tariff for stable employment and favorable conditions in the glass-workers trade.

And, by liberally spending tariff revenues on pensions for Civil War veterans and their families, the Republican coalition extended far beyond the industrial centers that benefited directly from the high duties. Those expenditures, both on Civil War pensions and on surveying Western lands, managing resources, clearing Native peoples, and protecting white landowners kept Midwestern grain farmers and Western ranchers, who paid higher prices for protected goods and lost access to export markets because of retaliatory tariffs from foreign powers, firmly in the Republican fold.

But for Gilded Age Republicans, the tariff represented much more than a ticket to prosperity. It also formed the foundation of Republican social policy. In their minds, it assured the health of the home and the virtue of young womanhood by sustaining higher wages and abundant employment opportunities that made it possible for men to support their families and women and children to fulfill their domestic roles. “Every woman should be a protectionist,” one GOP broadside proclaimed, because the tariff made “a more self-respecting and womanly life possible.”

While tariffs glued together different factions and interests, they also allowed the Republican Party to situate itself as the party of progress and national greatness—not Make America Great Again, but Make America Great in the first place. Even if the numbers didn’t really add up, the Gilded Age GOP embraced tariffs as an instrument to make people wealthier, safer and better behaved (reflecting the Protestant morality that dominated the party’s outlook). Flourishing business and secure workers would keep the Sabbath, dress neatly, and avoid taverns and other dens of iniquity that preyed on the degraded poor.

Whenever factional rivalries, regional tensions between Eastern and Western Republicans, or conflict between industrial and agrarian sections, threatened party unity, the tariff cemented them together. Leading Republicans like McKinley became adept at adjusting the rates to offer this industry a little extra protection or that veteran’s group better benefits or an area a railroad subsidy to dispel potential conflict.

Read More: Why Business Support for Harris-Walz Is Growing

In the early 20th century, the party deepened its historic attachment to tariffs. During the 1920s, Republican-led governments passed some of the highest tariff walls in U.S. history, a strategy that many scholars believe set off a wave of foreign retaliation that undermined efforts to relieve the Great Depression.

Several changes came after World War II. Some GOP leaders resisted change. Ohio Senator Robert Taft led an effort to kill plans for an International Trade Organization in the early 1950s, for example. But most GOP politicians embraced international cooperation and more open trade as part of the nation’s Cold War responsibilities to lead the “free world.” Later, with the election of Ronald Reagan and the embrace of free market conservatism in the 1980s up until the inauguration of Donald Trump, the Republicans reversed their historic protectionism to become champions of free trade.

Trump’s almost obsessive emphasis on tariffs, then, is not so much a reversal of economic policy as a revival of a tried-and-true cultural vision and a political strategy. Much like his 19th century predecessors, protection offers Trump an appeal to diverse constituencies: manufacturing interests, union laborers, declining industrial towns in swing states, voters without college educations and access to tech jobs. It also forms a coherent worldview with broad appeal: a nation victimized by insidious outsiders and the supposedly disloyal Americans who abet them.

That’s why neither sober economic analysis nor the outraged ridicule of Democrats will shake Trump’s fondness for and constant repetition of his favorite word. As Kamala Harris works to combat Trump’s appeal to state swing voters, the Harris campaign would do well to remember that tariffs are more a political strategy than an economic policy.

Bruce J. Schulman is the William Huntington professor of history at Boston University and author of The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Politics, and Society.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.