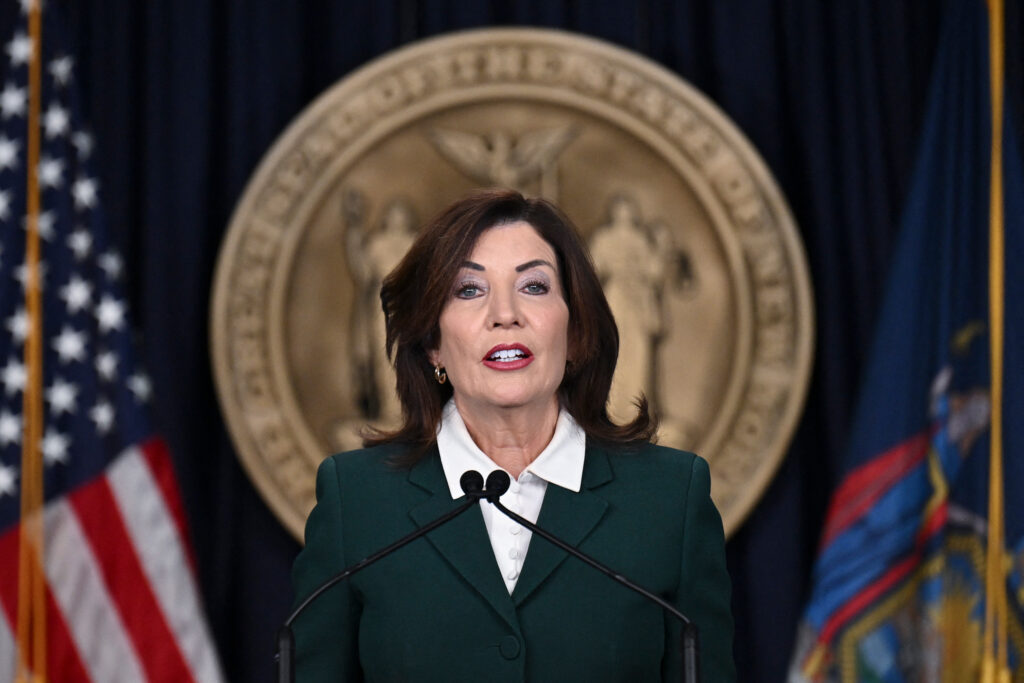

One month. That’s how long New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has to decide whether to sign a landmark environmental bill that would require fossil fuel companies to pay billions for the environmental harms caused by their greenhouse gas emissions.

The bill, dubbed the Climate Change Superfund Act, would establish a fund for climate resiliency infrastructure in New York, and require the large fossil fuel companies around the globe doing business in the state to contribute $3 billion annually for a total of $75 billion over 25 years for their role in creating “an immediate, grave threat to the state’s communities, environment, and economy,” according to the legislation.

If Hochul signs the bill, which the Legislature passed in late spring, New York would join Vermont to become the only two states with climate superfund laws on their books. New York’s law is based on the “polluters pay” principle established by the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, which gives the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency the authority to hold polluters accountable for the costs of environmental cleanup.

The $75 billion would help the state mitigate the irreversible consequences of climate change, including “rising sea levels, increasing temperatures, extreme weather events, flooding, heatwaves, toxic algal blooms and other climate-change-driven threats,” state lawmakers wrote. It would also shift some of the cost of paying for climate resiliency infrastructure away from the taxpayers and onto the broad shoulders of oil and gas companies riding high after years of record profits.

Hochul has not signaled support or opposition to the legislation. In the face of a second Trump presidency, many of the bill’s supporters see it as a way for the state to continue making progress on climate change.

State Sen. Liz Kruger, a Democrat from Manhattan and the bill’s sponsor, is “cautiously optimistic” that Hochul will sign the bill, said Justin Flagg, her director of communications. He noted the senator has not gotten any outreach on changes from the governor, and he called the superfund “even more significant in light of Trump’s election.”

“I hope the governor signs it,” said U.S. Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.), who in September introduced the Polluters Pay Climate Fund Act, a federal bill similar to the one on Hochul’s desk.

With Republicans controlling the House, Senate and the White House once President-elect Donald Trump is sworn in, Nadler said he was not optimistic about his bill’s chances of passing. “We have to keep up the fight,” he said. In August, Nadler released a statement urging Hochul to pass the Climate Change Superfund Act.

Hochul has a history of waffling on climate legislation. In November, she reversed course for a second time on congestion pricing in New York City. Initially, she supported the program before abruptly halting it weeks before its implementation earlier this year. After Trump vowed on X, formerly Twitter, to “TERMINATE” the plan his first week in office, Hochul quickly authorized a revamped version of the law with a lower toll.

Paul DeMichele, Hochul’s deputy communications director for energy and environment, said in an email to Inside Climate News that “the Governor is reviewing all legislation that passed both houses of the Legislature.” DeMichele did not respond to questions about whether Hochul supports the bill or if her views on it have changed ahead of a second Trump presidency.

Unlike congestion pricing, the Climate Superfund Act would not need federal approval (the former requires sign-off from the U.S. Department of Transportation) nor would it curb the proliferation of dangerous greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Instead, it is Albany’s way of acknowledging the severe cost of climate adaptation in New York, which will be necessary from Montauk to Manhattan, and from Buffalo to the Adirondacks.

Communities across the state are expected to spend billions on climate-related infrastructure over the next decade, according to the state Comptroller’s Office. Infrastructure improvements such as flood walls and stormwater basins in New York City and on Long Island alone could total upward of $200 billion.

Thanks to decades of climate change attribution science, researchers can pinpoint how much of the CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere has been generated by individual fossil fuel companies, and determine how those emissions impacted the likelihood of a natural disaster, like a hurricane or wildfire. For the purposes of New York’s climate superfund, any company or foreign entity extracting fossil fuels or refining petroleum products would be on the hook for a portion of $75 billion equal to their share of the total emissions between 2000 to 2018, the period covered by the law. Emissions from coal and natural gas are covered under the law, too.

For a company to be liable, its products must have emitted more than 1 billion tons of CO2 between 2000 and 2018, which means only the largest corporations would be affected.

The bill would do nothing to curb emissions, but dealing with the fallout of climate change is becoming increasingly important in New York. A few potential climate resiliency projects that could benefit from the superfund include stormwater infrastructure upgrades in New York City, updating parts of the state’s electrical grid, home weatherization improvements and climate resiliency projects along New York’s coastlines, in its forests and on its farms and fisheries.

At least $26.25 billion from the fund will go to projects that would benefit disadvantaged communities.

“It’s a good bill,” said Eric Weltman, a senior strategist and organizer for Food & Water Watch, an environmental advocacy organization that has been tracking the act. “It makes sense to have the fossil fuel industry contribute something towards the damages that they’re creating and profiting from.”

In 2023, Exxon, Chevron and Shell, three of the largest oil and gas companies in the world, reported combined profits of over $85.6 billion. If any of those companies end up on the hook for as much as $1 billion annually under the law, an unlikely scenario, it would represent less than 5 percent of their 2023 earnings.

In September, a group of business organizations, including the American Petroleum Institute’s northeast office, signed a letter to Hochul urging her not to sign the bill out of concern that it would raise energy prices for New Yorkers. The superfund “would create a recurring assessment that to me looks a lot more like an excise tax than a litigation expense,” said Ken Pokalsky, vice president of the Business Council of New York State, one of the organizations that signed the letter. “Why wouldn’t any current fuel marketer doing business in NYS today not think this will be applied to future fuel sales as well?” he said, in an email to Inside Climate News.

According to independent economists, these fears are unwarranted. Joseph Steglitz, a Nobel Laureate economist at Columbia University, wrote to Hochul in September to express his support for the legislation and to address any concerns she may have about its effects on gas prices.

“Concerns about the impact of the Climate Change Superfund on consumer prices are unfounded and should not affect your support for this critical legislation,” he said. Since the law would only target a company’s previous emissions, “it would not affect future production costs,” and therefore have no bearing on the price of gas.

Fossil fuel companies could not retaliate by raising prices for gasoline only in New York, according to a report authored by New York University’s Institute for Policy Integrity. “The interconnectedness of the national and global energy markets and existing U.S. antitrust laws” mean New Yorkers would be shielded from punitive responses by oil companies, the group said.

Pokalsky said that Hochul’s administration already has a climate funding source in mind, referencing a “cap and invest” program that would set an annual declining cap on emissions generated by utilities and distributors of heating and transportation fuels in the state as part of New York’s Climate Act, which requires net-zero emissions by 2050.

The two efforts are complementary, according to Jeffery Dinowitz, a Democratic state assemblyman representing the northwest corner of the Bronx and a supporter of the superfund. Since the superfund would target previous emissions, its purpose is to clean up “the mess that’s already been made,” he said. “The cap and invest program would, essentially, prevent future and further damage to the environment by way of climate change. So it’s two different things.”

“This bill is about achieving climate justice and making sure that New York taxpayers aren’t shouldering the entire burden of the costs of climate change.”

— Eric Weltman, Food & Water Watch senior strategist and organizer

Tens of billions of dollars over a quarter of a century still represents a fraction of the costs New York lawmakers expect the state to face as it adapts to climate change. Those expenditures could “easily reach several hundred billion dollars” by 2050, lawmakers wrote in the bill. And with Trump’s return to the White House looming, federal funding for such efforts may not be available.

“It would be useful to have [the Climate Change Superfund Act] on the books ahead of his presidency or during his presidency,” Nadler said.

Hochul “hasn’t given any indication to me, at least, as to whether she intends to sign it or veto it,” said Dinowitz. He is optimistic that she will “do the right thing,” and added that, while there are sure to be legal challenges to the bill from the fossil fuel industry should it become law, he is confident it would survive them. “Giving up $3 billion dollars a year would be a major, major mistake,” he said.

In November, the Federal Emergency Management Agency denied Hochul’s request for major disaster funding after 10 inches of rain fell this August during a devastating storm in Suffolk County, Long Island. “That’s FEMA under Biden. Who knows what Trump is going to do,” said Flagg, Kruger’s director of communications.

Food & Water Watch’s Weltman, who has called New York City home for the better part of the last two decades, worries Trump might go as far as withholding federal aid to combat natural disasters in states that did not vote for him. In that case, New York would be pining for legislation like the Climate Change Superfund Act, he said. “This bill is about achieving climate justice and making sure that New York taxpayers aren’t shouldering the entire burden of the costs of climate change,” Weltman said.

California, Maryland, Massachustts and New Jersey all have similar bills being developed by their respective legislatures.

Given the scope of climate disasters, the stakes of a second Trump presidency and independent economic assessments projecting little to no impact on the state’s economy, Weltman felt his governor’s mind should already be made up on the legislation. “Hochul has only one choice: side with New York taxpayers or the fossil fuel industry,” he said.

“I can’t fathom why she wouldn’t side with us.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,