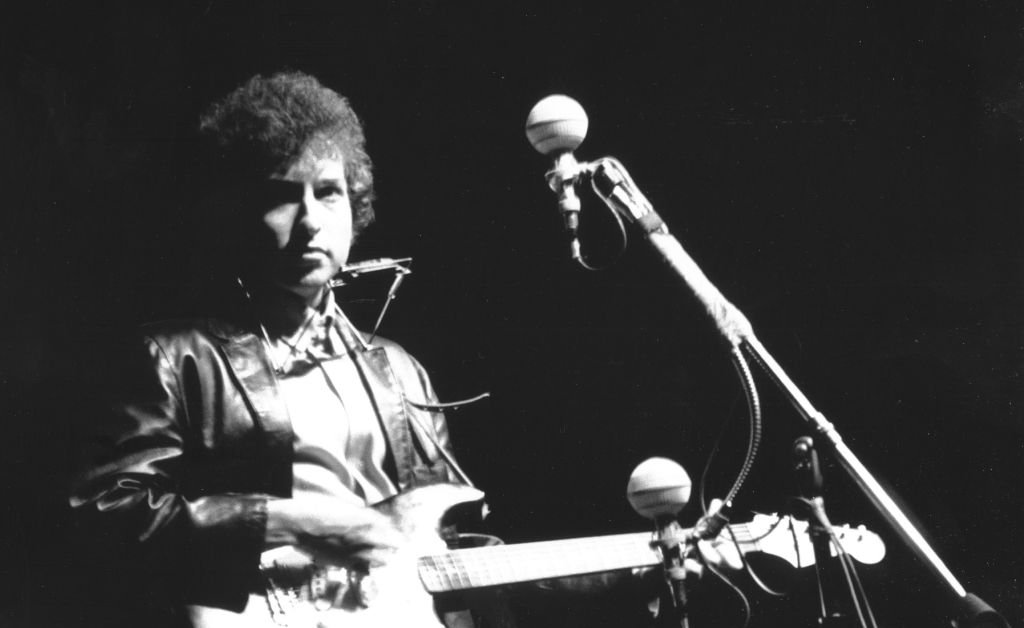

Toward the end of A Complete Unknown, the new film chronicling Bob Dylan’s early career, Pete Seeger and the young Dylan have a quiet but tense encounter. Anticipating Dylan “going electric” at the 1965 Newport festival, Seeger offers Dylan an extended metaphor about people working together for social justice, each person bringing a spoonful of sand to outweigh the force of injustice. Dylan, says Seeger, brought a shovel, with his powerful folk songs like “Masters of War” and “The Times They Are A-Changing.” Dylan rejects Seeger’s sermon, takes the stage, and blasts the old folk establishment with his electric Stratocaster.

According to the film, the Seeger-Dylan clash reflects the broader conflict between a musical tradition born out of the Old Left that brought together folk music and social justice causes, and the rise of a new musical sound, more experimental, far less political, and more closely keyed to the angry emotions of young Americans. It was, claims the book on which the movie is based, “the night that broke the Sixties.”

Not quite. There were a lot of things that “broke” the 1960s besides rock and roll: Black Power, Second Wave Feminism, drugs, and perhaps most significantly, the war in Vietnam, which also divided the folk music world. While popular memory of the 1960s assumes that folk fans and performers marched hand-in-glove with the anti-war protesters of the 1960s, in reality, the political climate of that moment, as well as the intensified commercialism of folk music, disrupted that alliance.

Read More: The 10 Best Movies of 2024

I have a historical interest in these events, and also a personal connection. My father, Irwin Silber, co-founded Sing Out! magazine in 1951, along with his close colleague, Pete Seeger. By the late 1950s, Sing Out! had become the go-to magazine for countless folkies—like the popular folk trio of Peter, Paul, and Mary; newer performers like Tom Paxton; and the “star” of the folk movement, Joan Baez. Long involved with left-wing causes, Sing Out! was also aligned with struggles for racial justice and international peace. My father wrote an irritated critique of Dylan in November 1964, chiding him for turning away from “protest” songs as he became more attached to the “paraphernalia of fame.”

But what concerned him most, in the summer of 1965, was not Dylan, but Vietnam. LBJ, having secured congressional backing in 1964 to promote U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, had dramatically increased U.S. troop presence in Vietnam from 23,000 to 184,000 and began an intense bombing campaign against North Vietnam in February.

Feeling the urgency of these events, Silber wrote to Pete Seeger ten days before Newport to discuss plans for a massive concert against this growing military escalation in Vietnam. Silber hoped to showcase several musical genres, including the Paul Butterfield band, several of whose members would be part of Dylan’s electrified backup band at Newport. At least in this “traditional” folkie’s mind, there was no meaningful divide between acoustic and electric. Rather it was about mobilizing music, no matter the form it took, to protest the war. In this way, Silber, not unlike Seeger, looked back to a tradition of joining music to political causes, whether it was the “Hootenannies” that protested the “Red Scare” in the 1950s, or the songs of the Black Freedom movement. The music in those cases had been broadly defined as “folk music,” although it often included blues, as well as singers who performed updated versions of popular standards.

The concert—held the autumn after Newport on Sept. 24, 1965, at Carnegie Hall and ultimately dubbed “A Sing-In For Peace”—played to a sold-out crowd of over 5000 attendees. Supporters included Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman, civil rights champion Fannie Lou Hamer, music critic Nat Hentoff, and over 60 musical performers, some of whom hewed more closely to “rock” than “folk.” At the end of the evening’s events, hundreds of attendees marched downtown to Greenwich Village to press their demands about military deescalation. Silber praised the way performers helped and supported one another, with each artist contributing to a larger “pattern that would most effectively address their government at a moment of urgency.”

This was an overly optimistic assessment on Silber’s part; the issue of Vietnam had already divided those on the folk scene. Peter, Paul and Mary, committed performers for Black freedom, were conspicuously absent from the event. Concert planners heard that the folk trio feared their civil rights work would be less “effective” if they took a stand on Vietnam. One-time supporters of the “Sing-In,” including Dylan and Odetta, also ended up being no-shows. Notably, they were managed by Albert Grossman—a highly unsympathetic figure in A Complete Unknown—who likely believed that anti-war protests were bad for business. By 1965, civil rights work had earned a public stamp of approval, even from the White House. Opposition to the war in Vietnam clearly had not.

Read More: The 10 Best Movie Performances of 2024

Not only did some performers, and their managers, object to an alliance between folk music and anti-war messages, so did many readers of Sing Out! Some were outraged to find foreign policy issues in its pages. With memories of Soviet actions during the Cuban Missile Crisis still fresh in popular memory, many saw the U.S. war in Vietnam strictly as a fight against Soviet- style communism. These readers had cheered Sing Out!’s position on racial justice, but Vietnam signaled a break.

As it traces Bob Dylan’s career in the early 1960s, culminating with his electrified performance at Newport, A Complete Unknown gestures towards some of the political chaos of the era, mainly with fleeting glances at JFK’s assassination or the 1963 March on Washington. The film has even less to say about Vietnam, making it hard to fully understand the substance behind the tensions of this moment.

In the Summer of 1965, Vietnam was, for some, an issue to be avoided: it was a messy political question that might also be bad for business. Yet for many others, the summer of ’65 presented a moment of reckoning: not about choosing acoustic or electric, but about responding to a brutal and unjust U.S. military escalation abroad.

Nina Silber is the Jon Westling professor of history at Boston University. She is currently writing a book about her family and the mid-twentieth century folk revival.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.